Standing up to the executioner

by

The Weekend Australian: 03 Dec., 2005 - On October 12, two days before he was due to die by lethal injection for murdering a former employee, Chinese tycoon Yuan Baojing took the precaution of signing over his 40 per cent share in an Indonesian oil field to the Chinese Government.

It was a bold and desperate move, but it paid off. The canny entrepreneur, one of China's first stock-market billionaires, must have known he had two things in his favour: China's desperate search for energy resources and its haphazard application of the death penalty.

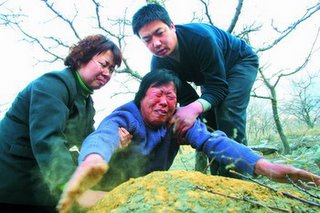

Yuan's date with death, 8.30am on October 14, came and went. At 11am he was allowed to see his wife and one-year-old son who had been waiting at the prison since early morning, fearing the worst. "I didn't know his execution had been halted until then," says his wife Zhou Ma. On the morning of his reprieve, Yuan smiled and laughed, and told his son to wait for him.

His wife says her husband is innocent and confessed under torture.

No official reason has been given for the 39-year-old's stay of execution, but few in China doubt his donation to the state, worth an estimated 50 billion yuan ($8 billion), had something to do with it.

"Legally speaking, it is not correct," says Huo Guoyun, a criminal law expert at the Political and Legal University in Beijing. "Donating to the country is not one of the conditions for the death penalty to be excused." But that doesn't mean it couldn't happen, he says.

China's fast and frequent use of the death penalty is under challenge from its citizens like never before. A debate kicked off by crusading lawyers and academics in the 1990s is running hot in the media and internet chat rooms, and the Government appears to be responding in measures the media has dubbed the "kill fewer, kill carefully" campaign.

Abolition of the death penalty is a "global unstoppable trend", says Tian Wenchang of King and Capital Lawyers, one of China's best-known advocates with one of Beijing's swankiest law firms.

In a long career he estimates he has rescued more than 20 clients from execution and lost a few less than 20 to it. Although many legal academics want the death penalty abolished, the rule of law "doesn't have a long history in China" so ordinary people are "not used to thinking in a legal way", Tian says. "It will really be a process to guide, to lead the populace to think in a legal way."

China's Supreme Court vice-president Wan Exiang said recently that abolishing the death penalty was "almost beyond discussion in China because the millennium-old notion of murderers paying with their own lives is deeply ingrained in people's lives".

But experts list a litany of problems that lead to many mistakes in China's use of the death penalty. For one, the courts simply don't attach enough importance to the life of ordinary people, Huo says. The death penalty is applied inconsistently, with standards varying widely from province to province and even court to court. Judges, many appointed as a reward for good service to the military or the Communist Party, often have limited knowledge of the law. Many are corrupt.

"It must happen" that a death penalty can be bought by your enemies and a pardon can be bought by your friends, Huo believes. Confessions are extracted under torture. Executions are often carried out with extreme haste, within a couple of days or even hours of the sentence being delivered. Appeals seldom succeed because they are heard by the same court that delivered the sentence.

A couple of recently exposed miscarriages of justice have boosted the case against the death penalty, including that of She Xianglin, who 10 years ago was sentenced to death for the murder of his wife. But in March the supposedly murdered woman turned up in their village, saying she had run away because she was tired of married life. Her husband was released four days later.

Every year China executes more people than the rest of the world put together, many times over. Exactly how many is a state secret, but Amnesty International's tally of execution notices in state media was 3400 last year, although it is probably 10,000. In the US last year, 59 people were executed.

China has 68 capital crimes. As well as rape, murder and killing pandas, they include non-violent crimes such as "separatism" (advocating independence for Tibet and Taiwan), "endangering national security", smuggling, tax evasion and corruption. Death sentences are administered by a bullet to the back of the head or, increasingly, by lethal injection. In the drug-rife southern border province of Yunnan, mobile execution vans were recently introduced to cope with the executioner's heavy workload.

Executions tend to cluster before public holidays and important Communist Party meetings which, according to state media, create a safer environment.

Huo says it will be at least 50 years before China gets rid of the death penalty, as most ordinary Chinese strongly favour it and officials depend on executions to keep the social order in the face of an upsurge in criminal activity among the poor caused by the growing wealth gap.

Meanwhile, lawyers are focused on getting the death penalty removed for economic crimes and getting the number of executions published. The number will be huge, but announcing it "will encourage China to raise the standard of the rule of law", believes Wang Shizhou, an academic lawyer at Beijing University.

Last month the Supreme People's Court said it would resume the right to review death sentences imposed by lower courts, which it forfeited to provincial courts in 1983 in a move to improve efficiency. Some say this could reduce executions by one-third.

But the problem remains that even if the Supreme Court recommends reconsidering a death sentence, the final decision rests with the original sentencing court.

So it was with Dong Wei, a 26-year-old peasant sentenced to death for murder in 2003. He was saved from the bullet with four minutes to spare after his lawyer managed to thrust his review request before a judge, who called the executioner by mobile phone just in time.

The lawyer said his client acted in self-defence when, pinned to the ground by three assailants who'd insulted his girlfriend, he groped for a brick. But when asked to reconsider the sentence, the Shaanxi Province Supreme Court decided its first judgment was sound and Dong Wei was executed.

No comments:

Post a Comment