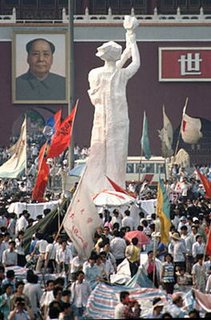

China braces for a year of sensitive memories

by Chris Buckley

Beijing, Reuters: 12 Jan. 2006 - China's Communist Party vigilantly guards its history, but in 2006 the country must navigate a cascade of traumatic anniversaries of Mao Zedong's rule that may provoke debate over its censored past.

Forty years ago, in May 1966, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution, the tumultuous mass campaign that spiralled into a decade of violence and repression.

The 30th anniversary of Mao's death is September 9. Then there is the October 6 arrest of the radical Gang of Four, marking the party's renunciation of the Cultural Revolution in 1976.

And amid all this, there is the Tangshan earthquake, which 30 years ago on July 28 leveled the city in north China, killing at least 240,000 people and laying bare the country's weakness and isolation after decades of political campaigns.

Today the Communist Party still strictly guards the country's archives of those times and restricts books about the Cultural Revolution. Party scholars said they expect few new works to make it past censors, even in this year of anniversaries.

"The central leadership doesn't worry about history for its own sake, but they don't want to look like they're encouraging doubts about the party when there are already enough doubts," said one Beijing researcher whose study of the Cultural Revolution has been blocked for years.

But Zhang Guangyou, a retired reporter who witnessed many key episodes of the Cultural Revolution, said recalling those years may help China change for the better.

"History offers lessons we all need to remember, and leaders who remember the past will understand how much we need more reform, more change," Zhang told Reuters.

PURGES, WARFARE

Zhang, 75, worked as a reporter for the official Xinhua news agency for much of the Cultural Revolution, when Mao summoned the country into frenzied, often violent struggle against "capitalist roader" officials accused of betraying the revolution.

Hundreds of thousands died in purges and bouts of warfare, including Mao's one-time designated successor, Liu Shaoqi, who died in prison.

Zhang filed dispatches to China's leaders about fighting between rival Red Guard factions in Beijing universities and the kidnapping of Liu's wife, Wang Guangmei, as well as cannon battles between rival radicals in the western Shanxi province.

He also covered the ruin of Tangshan.

"The whole city, everything, was devastated. There was nothing left standing. You couldn't tell the living from the dead," Zhang said of Tangshan. He was among the first reporters to arrive after the earthquake, by a Mercedes Benz driven 220 km (137 miles) southeast from Beijing.

Zhang has written memoirs of four decades of reporting, but he does not think the manuscripts will be published this year.

Maybe in a few years, maybe sooner," he said.

Zhang said he has no nostalgia for those times, but like many of his generation he recalls a deep, often-unquestioning loyalty to Mao that survived even the Cultural Revolution.

"We all had deep feelings for Chairman Mao. We admired him for unifying China," said Zhang, recalling his death. "I also knew he committed errors and even misdeeds, but back then we were all shaped by long-term propaganda."

The fear that renewed scrutiny of Mao's legacy may erode the Communist Party's standing still dominates its handling of the past. While researchers continue to write, much of their work appears only in Hong Kong or Taiwan -- away from mainland readers -- or is never published.

In 1981, the Communist Party, under the new reformist leader Deng Xiaoping, issued a "Resolution" on history that set the party's official verdict on its past and Mao's legacy.

Deng said that Mao was "seven parts correct, three parts error," and fended off calls from some officials persecuted under Mao for a full renunciation of the past.

Since then, the party has declined proposals from aging officials for a new resolution that reflects the country's rethinking of its past, Zhang said.

Chinese critics of the government said they may organize memorial meetings about the Cultural Revolution later this year, but many younger people have little interest in the Mao era.

No comments:

Post a Comment